Russel starts out this story in a very dull and monotone way. Her first sentence is a suggestion of excitement, but she quickly negates it with “but of course there is no way for anyone to verify that now.” She then goes on to write a long list of the characteristics that all of the worker women share. This tone sets up an intriguing contrast with the outlandish happenings of the actual story and allows the reader to suspend disbelief. There is no feeling of silliness that goes along with reading about a group of women who have turned into silk worms because we are made to understand early on that there is absolutely nothing exciting and joyful about it.

Through the story of Kitsune’s eagerness to impress the man who got her in the terrible situation she is now in against her better judgement, Russell opens the story up to more interpretation than a simple story about women being victimized by a terrible man and having to make the most out of a situation which they are stuck in. The focus on daydreaming and comradery initially seems to push the story in that direction, and right up until Kitsune’s sudden turn to tenacity the story feels safe even despite the fact that these are “silkworm-women” and it feels as if it could easily end with Dai’s death as the final proof that these women must simply learn to live with what they have. Once the reader hears those fateful words, “if the caterpillars are allowed to evolve, they turn into moths. They grow wings and teeth,” the reader is shocked and excited, not having seen any way out and having been lulled into just as much of a dull and somewhat indifferent acceptance as the kaiko-joko (she does this by using monotonous language, describing the glimpses of pride that Kitsune occasionally feels for being the only group of people able to spin so much silk, the idea that important people are wearing it, and the sense of individuality that they get from having distinct colors).

The question of how far willpower can take a person is posed, tested, and ultimately triumphs. The wings, however, never actually grow during the story, and the ending focuses more on revenge than the gaining of freedom. To me, the choice of ending the story with the Agent’s death was disappointing and brought an abrupt halt to the triumphant feeling that Russell had evoked through the rapid change of tone from the monotonous plodding of a group of defeated women to the rush of a revolution. The ending gave me a sense that the writer was keeping a secret from her readers, that maybe they never did get their wings, or maybe they got them but were never able to escape the room, starving to death, or once out they were just as miserable being trapped in their moth bodies as they had been trapped in the room. If the writer was trying to give us a clue as to what happens next and not simply leaving us in the dark, I can only guess that by leaving us with the image of Kitsune’s moth-face reflected in the eyes of her dying victim, Russel is suggesting that the women are losing their humanity and by incasing themselves in thread created by their own bitterness and regret, they will ultimately emerge as complete monsters. This is, again, a very abrupt change in what had seemed to be the direction of the story and is both frustrating and intriguing.

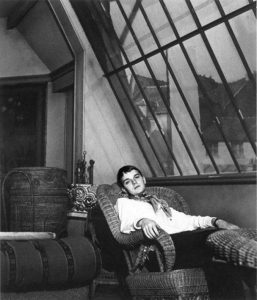

Hilton Als’ essay “The Women” is roughly about the author and filmmaker — and artist in many other senses — Truman Capote whose first book was published in 1947. Als stresses that this publication takes place “just when other ‘real’ women could not as freely enter the publishing world” (238). Als characterizes Capote as a woman because of the feminine voice and sensuality of his writing, as well as because of the topics he chose to write about. His book Other Voices, Other Rooms featured a photo of Capote on the back cover, which Als states was “something to be fucked somehow.” The qualities Als describes are Capote’s manicured hands and his intrigued expression or perhaps even the writing of other women (238). Als claims Capote never wrote as himself, and within the essay itself Als doesn’t write much about the mundane aspects of Capote’s life. This leaves only the parroted writing style and interviews for the readers to make assumptions about Capote as a person apart from his work.

Hilton Als’ essay “The Women” is roughly about the author and filmmaker — and artist in many other senses — Truman Capote whose first book was published in 1947. Als stresses that this publication takes place “just when other ‘real’ women could not as freely enter the publishing world” (238). Als characterizes Capote as a woman because of the feminine voice and sensuality of his writing, as well as because of the topics he chose to write about. His book Other Voices, Other Rooms featured a photo of Capote on the back cover, which Als states was “something to be fucked somehow.” The qualities Als describes are Capote’s manicured hands and his intrigued expression or perhaps even the writing of other women (238). Als claims Capote never wrote as himself, and within the essay itself Als doesn’t write much about the mundane aspects of Capote’s life. This leaves only the parroted writing style and interviews for the readers to make assumptions about Capote as a person apart from his work. Go

Go  This story is very intriguing because it turns the Vampire myth on its head and makes it a source of pain and development for the character’s love story. The reader feels sympathetic to him because he does not desire to be a monster and was shaped by the Western/Eastern Vampire myths. His fear of acting as a Vampire should almost mirrors the fear the older woman had in the cemetery of what Vampires are known to do. He states, “The lemons relieve our thirst without ending it, like a drink we can hold in our mouths but never swallow. Eventually the original hunger returns. I have tried to be very good, very correct and conscientious about not confusing this original hunger with the thing I feel for Magreb” (8). What I found really effective is the description of his fear of the sun and his being convinced he would burn. His behavior is not merely dramatic because he later realizes the foolishness of it and how it inhibits him from moving forward. He feels safe in the myth and is comforted by what he sees as an instinctual need for blood. The sentence structure as he makes his way out of the cellar raises the anxiety for the reader. “Afraid, afraid” seems to echo mores through his mind than on the page (11). He sates “Thirty years. Eleven thousand dawns. That’s how long it took for me to believe the sun wouldn’t kill me” (13).

This story is very intriguing because it turns the Vampire myth on its head and makes it a source of pain and development for the character’s love story. The reader feels sympathetic to him because he does not desire to be a monster and was shaped by the Western/Eastern Vampire myths. His fear of acting as a Vampire should almost mirrors the fear the older woman had in the cemetery of what Vampires are known to do. He states, “The lemons relieve our thirst without ending it, like a drink we can hold in our mouths but never swallow. Eventually the original hunger returns. I have tried to be very good, very correct and conscientious about not confusing this original hunger with the thing I feel for Magreb” (8). What I found really effective is the description of his fear of the sun and his being convinced he would burn. His behavior is not merely dramatic because he later realizes the foolishness of it and how it inhibits him from moving forward. He feels safe in the myth and is comforted by what he sees as an instinctual need for blood. The sentence structure as he makes his way out of the cellar raises the anxiety for the reader. “Afraid, afraid” seems to echo mores through his mind than on the page (11). He sates “Thirty years. Eleven thousand dawns. That’s how long it took for me to believe the sun wouldn’t kill me” (13).